In a Thrilling New Show Artist Cathrine Raben Davidsen Explores the Beauty and Terror of Life

By Laird Borrelli-Persson for Vogue

It’s easy to imagine surprise being the primary reaction of visitors to the mid-career survey of Cathrine Raben Davidsen’s work at Copenhagen Contemporary this week. This popular Danish artist is best known, and loved, for her beautiful, yet eerie works, many of them pretty portraits, drawn with a line that looks fragile, but which carries the weight of mythology. The beauty of these drawings takes the viewer into unexpected, often uncomfortable places, but none as dark as those on view in the new exhibition, “Let Everything Happen to You.” The exhibition opens at a time when many have a sense of hopelessness as to current events; at a time when glossy images of so-called perfection serve as pacifiers, but not cures.

Davidsen, who studied theology, is an artist whose process often starts with the creation of mind maps. She reads a lot and the title of the exhibition comes from a line of poetry by Rainer Maria Rilke from the poem “Go to the Limits of Your Longing”: “Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.” It can be understood to be an admonition to embrace life in all its extremes and messiness, and Davidsen does this through her art.

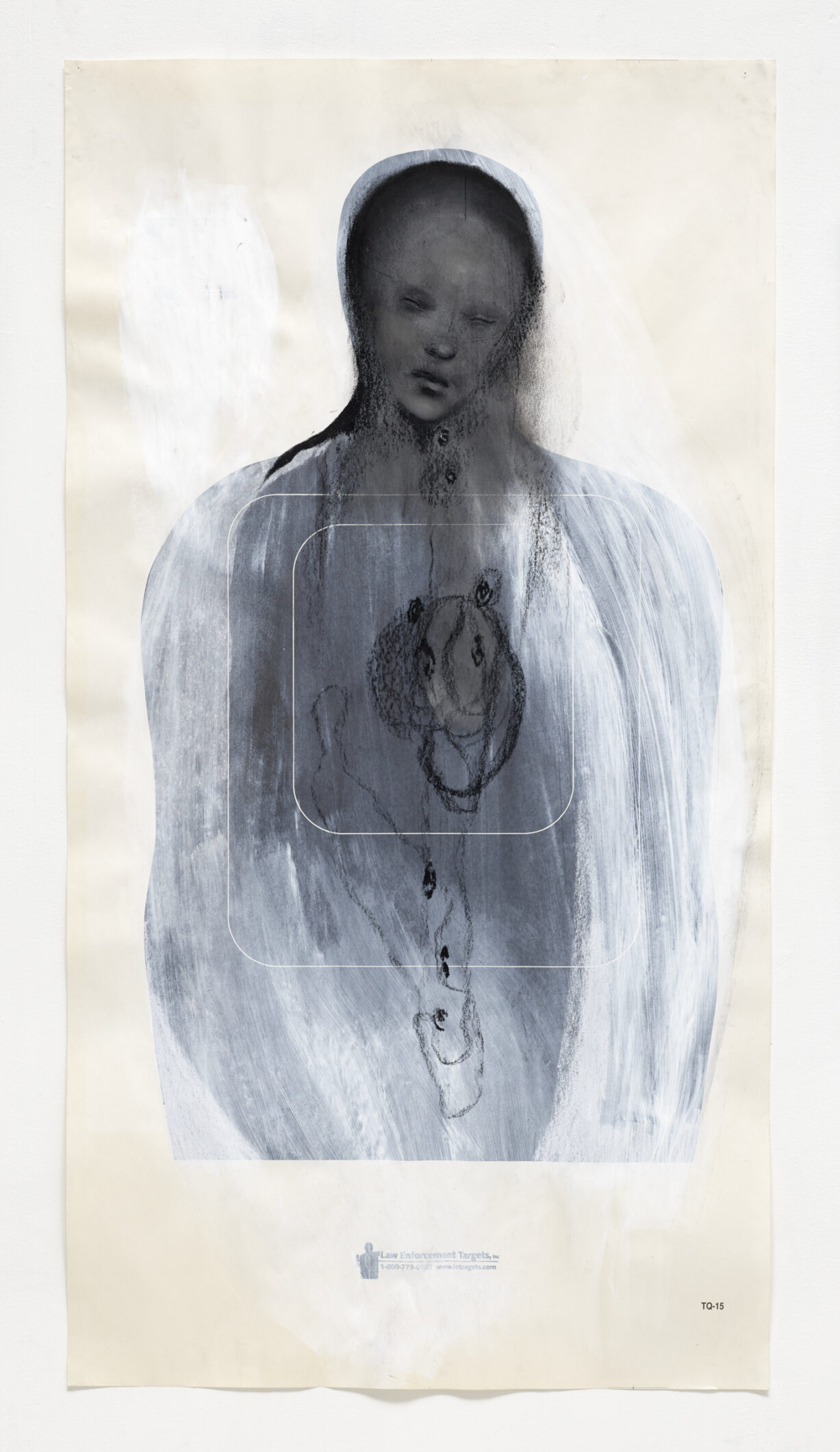

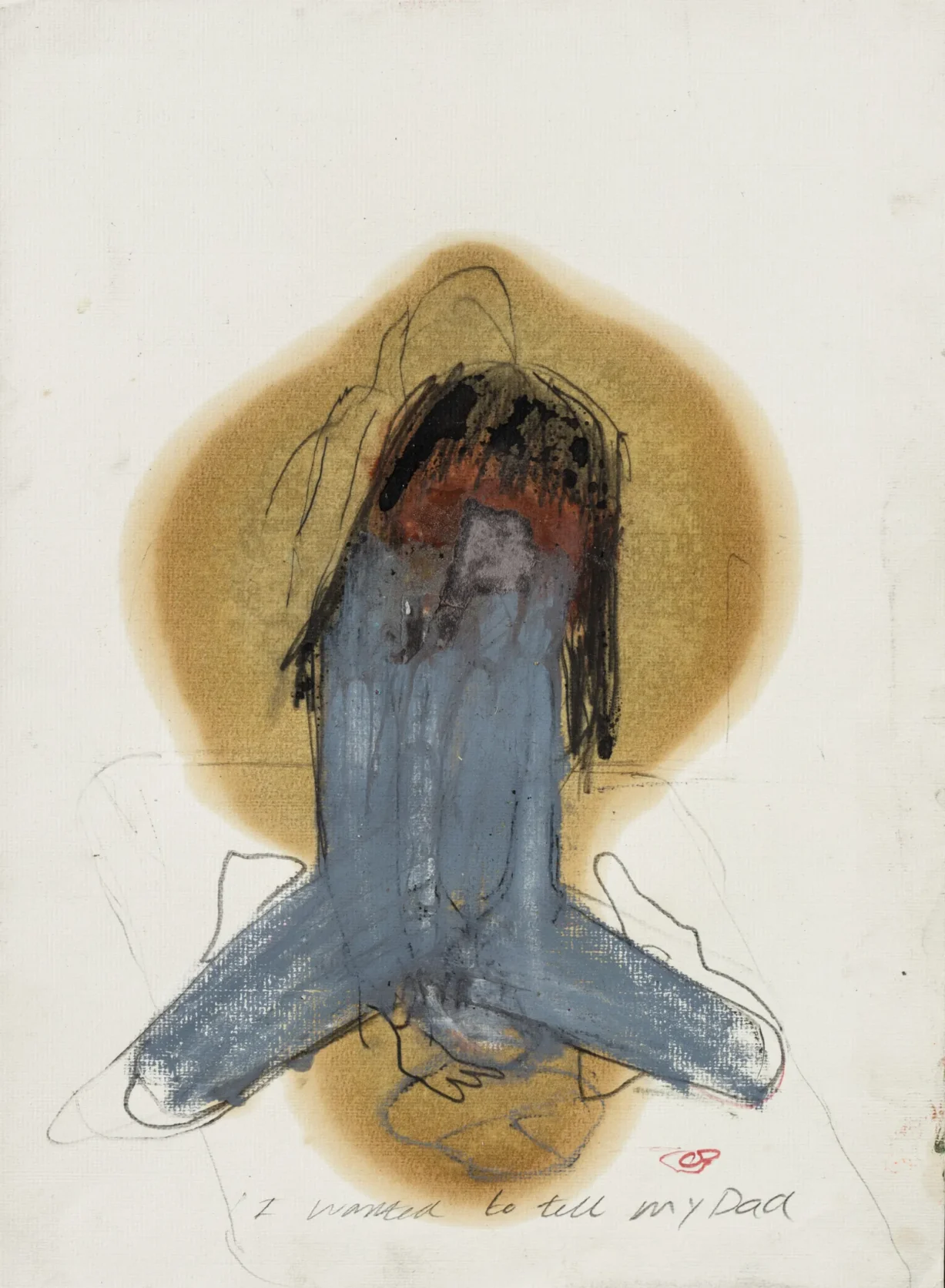

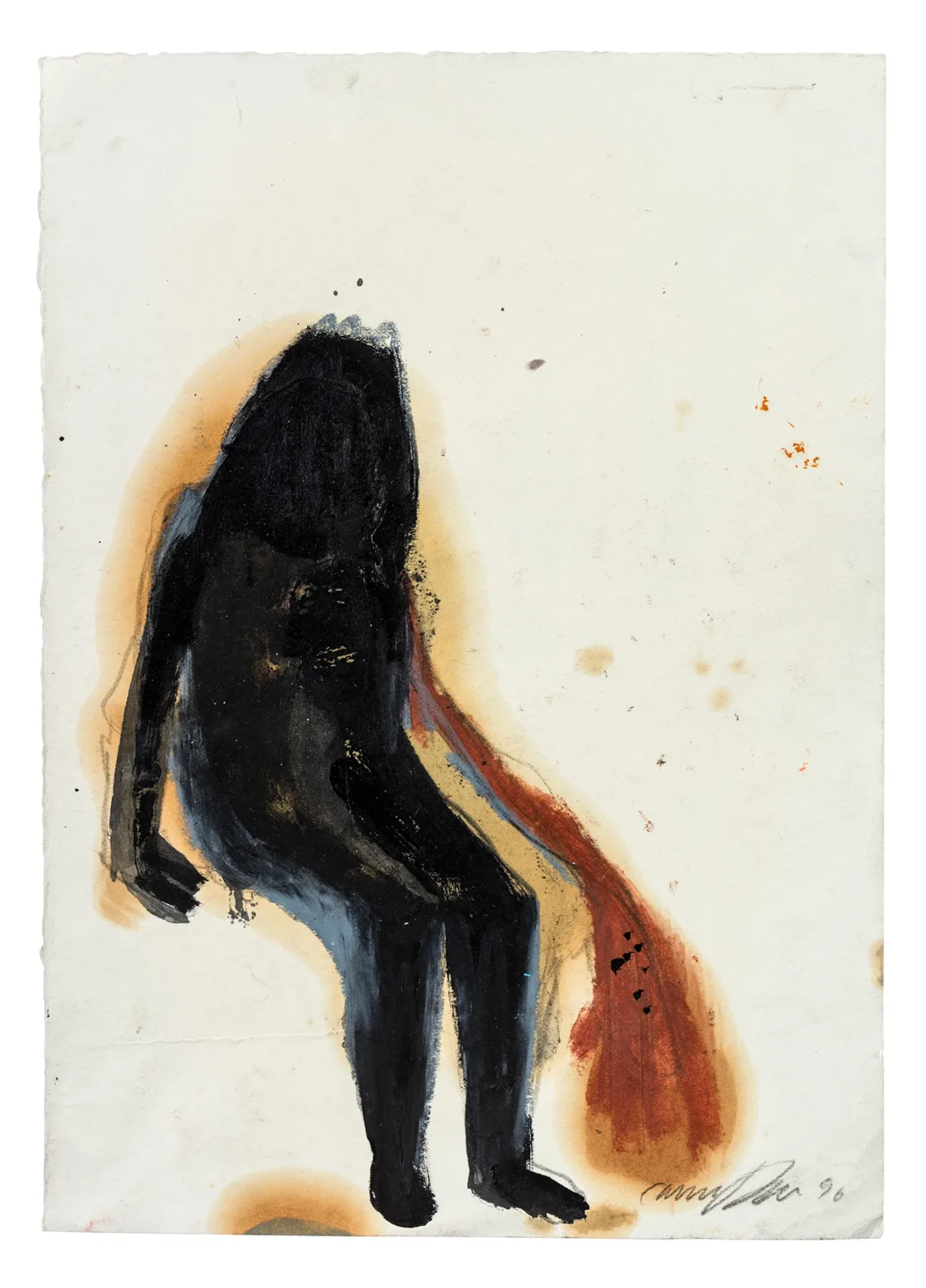

While not organized as a retrospective or strictly by chronology, the exhibition moves from the personal to the universal, with a concentration on the works on paper created by the artist in the 1990s as she tried to come to grips with the death of her father, when she was just 13. A bisexual, he was one of the first Danes to die of AIDS. “All the works are made ten years after he died. I wasn’t ready, I didn’t know anything when I was 13,” she says. “I began painting as a way to connect to him because of the loss, and also the confusion. Everything was a secret, and it was so shameful.” It can be uncomfortable to look at these early works. They are controlled and wild at once, deliberate and emotional, with lines that are thick, raw, and coarse—primal screams on paper.

The decision to show this challenging work was a deliberate one by museum director Marie Laurberg and curator Aukje Lepoutre in coordination with the artist. “Giving a big show to a local artist means we want to contribute with an angle on her work which gives a new impression of it–and lifts it into new conversations,” says Laurberg. “Cathrine is a very technically skilled painter, and she does create works that really make your heart jump. But she has this other, more brutal side, which is maybe not always that obvious. We wanted to bring that side out more.”

“I really am known for those pretty pieces,” Davidsen admits. “But I’ ve always been interested in what lies beneath and the dark stories. I’ve always been attracted to the darkness.” Is there finally room for female artists to show work that isn’t conventionally beautiful? “I don’t want to necessarily answer that,” Davidsen responds. “I can only speak for myself, and for me, I’ve never been interested in my sex, or if I’m female or masculine. I think actually I’m more masculine than feminine in a sense, the way my brain works.”

Laurberg has a more direct perspective. “I want to show the next generations that women can–and should!–take the big stage,” stated the director who recently curated the Mamma Anderson exhibition at the Louisiana Museum. “A new generation is taking over leadership, and there is a strong sense that we are not here just to repeat the old music. For me it is pretty clear: I want to use my position to change the narrative for women in the art world. When I first started working in curatorial positions in large institutions 20 years ago,” she continued, “I repeatedly witnessed women artists being surpassed, undervalued, not invested in. This was not done on purpose, as part of some evil plan. It was based on deeply ingrained ideas in culture about the artist, what a genius looks like, and in the end–which stories are part of what we call the human condition.”

In the last few years, Davidsen has made a more visible move from the personal to the universal with her paintings of landscapes. “It began around the pandemic time, when nature was taking over us humans, in a sense. … Ever since The Vitruvian Man, the Leonardo da Vinci figure, the figure has been in the middle and the figure has been dominating the whole world. … Making the landscapes was a way of removing myself and all people from my work; I wanted to get rid of all the people and to give a voice to nature.”

All of the landscapes have the title “As above, so below,” which comes from an ancient text, and might suggest a Dantean reading. The largest work in the exhibition is a dense, tactile painting based on a satellite picture of destruction through war. “When people came in and saw the work when I was making it, they were like, ‘Oh my God, it’s so beautiful.” When the viewers learned the title, “Crater Scar,” their opinions changed, says the artist. “It’s interesting to play on that—the beauty and the horror of it—and that’s also what’s the essence of the Rilke poem. He’s saying, ‘Don’t let yourself lose me, whether it be beauty or terror, you have to go into it.’”

In one drawing in the show, a hand is reaching down to lift another up, in a gesture of welcoming, of succor, of assistance. “Give me your hand,” is the closing line of the Rilke poem that guides the show. Davidsen’s exhibition is similarly a lifeline. It might not always be easy to hold onto, but it offers a valuable and moving connection.

Cathrine Raben Davidsen’s “Let Everything Happen to You” is up at Copenhagen Contemporary from January 25 through May 12 2024

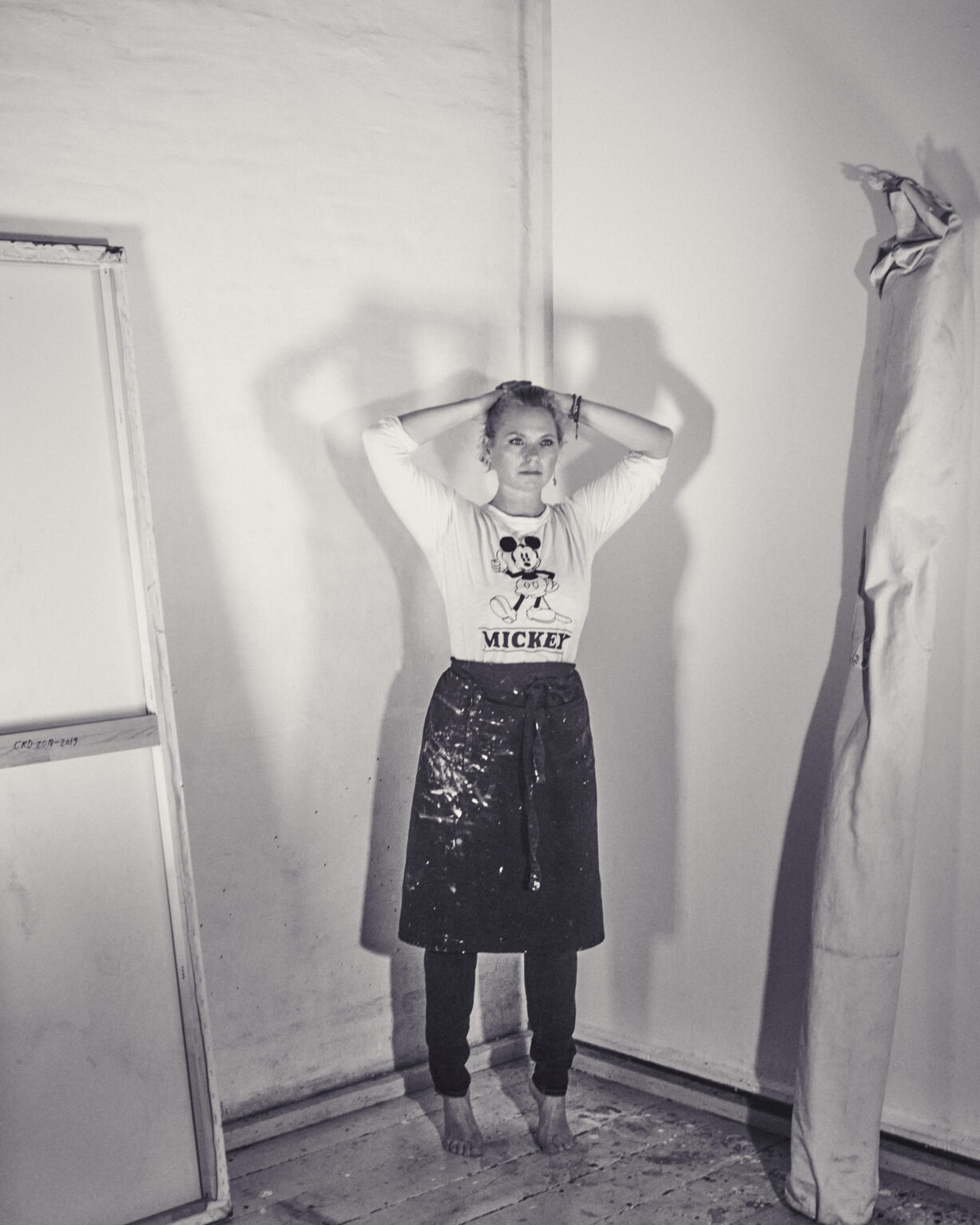

Portraits of Cathrine Raben Davidsen, 2024. Photo: Casper Wackerhausen-Sejersen; make-up, Anne Staunsager.